Inflation, a term often heard yet seldom fully understood, is an economic phenomenon that impacts virtually every facet of our lives. It affects our purchasing power, the value of our savings, and even our economic outlook. But what is inflation, really, and how does it occur? Let’s dive into a comprehensive analysis of inflation from an Austrian Economics perspective. If you haven’t read the “what is money” section, it would be beneficial to read this first prior to this particular article.

What is Inflation?

Most people understand inflation as a price rise. To be more specific, it is the price rises in all goods and services.1 This is generally quantified as a percentage annual rise in price. For example, if the inflation rate is 2%, this means prices for goods and services have risen around 2% compared to the previous year. If you paid $5 for coffee last year, it would cost you around $5.10 this year.

Given what we know of the concept of money from our previous articles, let’s explore money as a good like any other.

Decoding Inflation: The Supply and Demand Equation

The more interesting question is “what causes inflation?”. To the Austrians, inflation is not merely an increase in prices; it is an increase in the money supply.2 Here, we part ways with the mainstream definition of inflation as the annual percentage increase in the average price of goods and services. Instead, we align with the Austrian viewpoint that inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon.2 This perspective lays the foundation for our discussion and shapes our understanding of the dynamics at play.

If you’ve heard that a war between two countries that have 2% and 0.2% of Global GDP is the reason for wide spread inflation, you’ve been lied to. I’ll leave this short clip to demonstrate the contrast in inflation narrative between politicians and Austrian Economists.

A hypothetical Economy

Let’s explore using an example of a small hypothetical economy. Say you were in an economy with a fixed amount of dollars and just three purchasable items (houses, apples and paper). It’s a fairly boring market, but one day something happens to the production of apples. It was found that pests wiped out a lot of the seasons apples and resulted in a supply shock. If people still wished to purchase the same number of apples, you would get a price rise in Apples due to a reduced supply. Apples go from $4 to $5.

Because this is a hypothetical economy that has a fixed number of dollars, it means that there is a drop in demand for houses and paper at any given instant. Why? because consumers have spent that extra dollar on apples and can no longer be spent on houses or paper. So if supply remained the same for houses and paper, you would expect a reduction in price for both those goods due to a reduced demand.

When looking through this lens you can see that the demand side of the equation is how many dollars people give up for that good or service. If you have no money, you do not contribute to demand no matter how much you want something.

Demand = Number of Dollars people gave up for a good or service

Supply = Units of Goods Available for purchase

Now say we had a supply issue for apples, houses and paper equally, but demand remained the same. Given there is a fixed number of dollars in this economy, what happens to the prices? Here you get inflation. But for this to happen, there must be a reduction in supply of ALL goods and services. However, given how technology is making goods and services cheaper and easier to produce over time, this is a diminishingly unlikely cause for inflation.3 In an economy with a fixed supply of money that experiences the exponentially deflationary pressures of technology, it would be unlikely to experience any inflation at all.3

A simple way to frame inflation is the ratio of dollars to goods/services. If that ratio is increased (increased dollars or reduction in all goods/services) the economy will experience the phenomenon of inflation. The most likely culprit for inflation, therefore, is the increase in the monetary supply.4

The Rational Free-Market

As discussed in the previous articles, money is like any other good. It is the good that is most easily exchanged (saleable) for other goods. So how do monetary goods work in inflation?

The short answer is, they don’t. When the supply of any good increases, its value generally decreases relative to other goods in a market.5 Monetary goods are no different.5 When consumption goods and capital goods increase in supply, this reduces prices for those goods. This is generally a good thing for society. This makes things cheaper relative to money and therefore more accessible to a greater number of people.5 Increasing the supply of a monetary good, however, will do the opposite. It makes goods and services more expensive relative to the money and therefore accessible to fewer people.5

money needs to store Value

When money fails to act as a good store of value, people will naturally dispose of it in exchange for a better store of value. This occurred over thousands of years with commodity money such as copper, silver and gold where copper and silver’s monetary premium diminished relative to gold over time.5 Scarcity appears to be a strong property of money and the consequences of breaking this property have had dire consequences throughout history.5

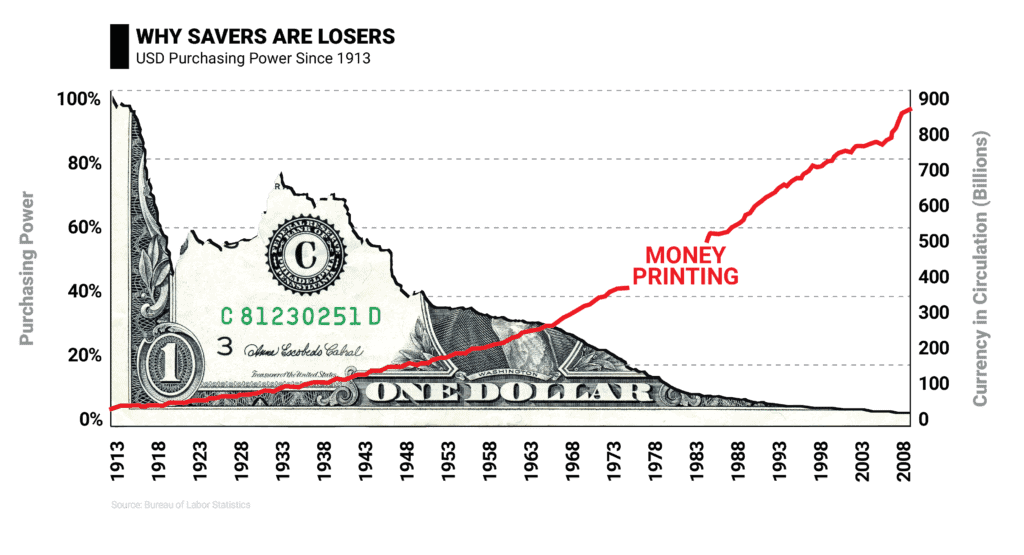

As the money supply grows, the relative value of each unit of currency decreases, and this diminished purchasing power manifests as higher prices for goods and services.4 So as fiat currencies get printed away, people will dispose of them for scarcer assets.4 You can see it happening in real time.

Relative Scarcity

The inflation rate is a rough estimate. As many millennials have noticed, house prices are significantly higher than many inflation figures. There are several countries that have house prices exceeding 20% annually.6 This discrepancy between price rises in individual goods and services occurs as the more scarce assets absorb much of the price rises as people find scarcer and better stores of value.5 Inflation is the market collectively deciding that everything else is a better store of value than dollars themselves. It is the result of the free-market making rational economic decisions when faced with currencies with a seemingly unlimited supply.5

Keynesians and the Benefits of Inflation

Keynesian economists argue that a moderate inflation rate can carry certain benefits, a viewpoint that is rooted in the Keynesian belief in active government intervention to “stabilise” economies.7 They argue that an inflation rate of 2% can stimulate economic growth by encouraging spending and investment.7 The general premise is that in a state of expected inflation, consumers are incentivised to purchase goods and services now rather than later, when prices are likely to be higher.7 Similarly, businesses may be encouraged to invest in new projects today to avoid higher costs in the future.7 This perspective is flawed in several ways.

First, it assumes that consumers and businesses can accurately anticipate inflation and adjust their behaviour accordingly. In reality, inflation often catches people off guard, eroding their purchasing power.4 This is even true of the US Federal Reserve which has publicly and poorly predicted economic outlook. They had gone from “we don’t expect to experience any inflation” to “Inflation is transitory” to “Inflation might be present for a while” in a matter of months. The Reserve Bank of Australia also stated it was not expecting to increase interest rates for several years, only to increase them aggressively mere months after the statement to combat inflation. If such institutions can’t predict inflation, how could anyone expect individuals and businesses to?

Second, it overlooks the negative impacts of inflation, such as income redistribution effects and distortions in relative prices, which can lead to resource misallocation.4 Spending more isn’t necessarily a good thing if the reason people are spending is to dispose of the dollar rather than to invest in a particular company or project.4

The more pessimistic reason for having a 2% inflation rate is to steal purchasing power from fiat currency holders to enrich governments. You could think of this as a 2% annualised compounded tax… without calling it a tax.4,8 These compounding effects are enormous with many fiat currencies devalued greater than 95% over the last century, including the US Dollar.

During this period of significant inflation It’s important to remember that even if inflation returns to 2%, this just means that goods and services are 2% more unaffordable than they were the year before. To return to more affordable costs of living we would need deflation.

The Cantillon Effect: The Real Cost of Inflation

The economy is a closed system where there are dollars and goods/services.9 The individual units of dollars themselves aren’t as important as what they can buy you. After all, the greatest utility of money is the ability to exchange it for something else.5 We call this purchasing power. Purchasing power is similar to energy in that it cannot be created or destroyed given the dynamics of a closed system.9 So if all this purchasing power is being eroded from fiat currencies, where does it go?

Contrary to popular belief, inflation does not affect all prices equally.10 The Austrian school points out that new money enters the economy at specific points, impacting different sectors at different rates.10 The first recipients of the new money – typically the government and the financial sector – benefit from high purchasing power.10 As this money filters through the economy, other prices start to rise, and by the time it reaches ordinary consumers, they face increased prices without the benefit of increased income.10

In this landscape, anyone that holds scarcer assets than fiat currencies will benefit from inflation and those that hold the scarcest assets will benefit more.10 These can include assets such as houses and commodities. You can imagine if you were wealthy, you’d probably store greater than 90% of your wealth in such assets, and whatever leftover in cash. If you were poor, you’d be lucky to get by day to day with what little cash you have and likely have most (if not all) of your wealth in cash.

Inflation essentially re-distributes wealth from those that hold cash (mostly poorer people) to those that hold assets (mostly wealthy people). Inflation is the single biggest contributor to wealth inequality.10,11 This is the Cantillon effect, first described by Richard Cantillon in the 18th Century.10 Although he described it in relation to commodity money such as gold, his theory still holds true today.

“No matter who obtains the new money, it will more or less be directed to certain kinds of commodities or merchandise, according to the judgement of those who acquire the money. Market prices will increase more for certain goods than for others.”

The biggest benefactor of inflation, however, is the government. This newly created money without cost first enters at the government level, allowing them to gain the most purchasing power at the expense of those who hold cash.11,12 While the official stance is that this money helps stimulate the economy, it often widens the wealth gap and exacerbates societal problems.11 Despite their efforts to mitigate the effects of inflation, governments inadvertently intensify it, leading to a vicious cycle that historically has often ended in complete erosion of the currency and societal collapse. The concept of using newly created money to redistribute it to an economy efficiently is the general pretext but here lies the paradox.

“Its like the government broke your leg with a pair of crutches, and you thanking them for gifting you those very same crutches”

Governments create a bigger inequality gap by printing money and exacerbating inflation.11 This in turn makes the cost of living harder for poor people and easier for wealthy people.11 Society in general will complain the government is not doing enough but simultaneously be upset with higher taxes. The response by the government is as predictable as the seasons themselves and will try to “help” those most affected by printing more money to fund social programs rather than cutting costs elsewhere. The irony is that by doing so exacerbates the primary problem.11

Although the Cantillon effect is well observed, this example was used to simplify this concept. The economy is not an entirely closed system when discussing individual countries. In the context of a global market, however, it could be considered a completely closed system as there are no market participants outside of this. Let’s look at inflation and the Cantillon effect from a global perspective.

Inflation: America's Biggest Export

Having your country’s currency as the global reserve asset has its benefits. Because many international commodities are priced in the US dollar, other countries would have to sell their local currency to purchase US dollars in order to then purchase these commodities.13,14 This essentially devalues their currency relative to the US dollar while simultaneously increasing demand for the US dollar.13

This increased demand is what allows the US to print such an exorbitant amount of dollars without causing a proportional devaluation of the US dollar.13,14 On top of this, many countries devalue their own currency relative to the US dollar intentionally in order to make their exports more favourable for trade.13,14

Lastly, there is increased demand for US Dollars as the weakest currencies of the world hyper-inflate and collapse.13,14 These countries and their citizens are faced with the desperate need for a stable currency for the country to function. Once their own governments are done siphoning the wealth and productivity of their citizens through the irresponsible creation of money, they are forced to relinquish their control of the local currency by instating a more stable foreign currency outside of their control.13 The US dollar, as they say, is the cleanest shirt in the dirty laundry and is the usual choice.

In this scenario, the US is able to print money without a relative increase in inflation to the US dollar because that inflation is absorbed by all the above factors.13,14 In essence, what this means is the US is now not only able to steal purchasing power from US dollar holders but is able to steal proportionally more from those holding other currencies including other governments. Those that are most affected, of course, are the citizens of other countries who have had their purchasing power stolen twice. Once by their own government through inflation of their local currency, and a second time by the US as their governments are forced to sell their currency for US dollars.13

If you think about inflation, the same principles of the Cantillon effect apply on a global scale. Those governments that benefit the most would be those of countries that have scarce assets that disproportionately increase in value in the face of global inflation. This would be mainly commodity-rich countries such as Saudi Arabia, Australia, Russia, and Brazil. The greatest benefactor, however, is the US government. Our current global economic system not only creates a widening inequality gap within individual countries but also creates widening inequality amongst countries globally.

Conclusion

The basic concept of inflation is simply the imbalance of demand compared to supply of dollars to goods. By allowing governments to print money, we allow them to impose a hidden tax on everyone earning in the local currency.4,8 A hidden tax that was not voted for. In most cases, it is decided by a handful of people in the government which is also the institution set up to gain the most from such decisions. This also disproportionately affects poorer citizens negatively and benefits wealthier ones.10

The US Dollar has such high demand from several factors (including some discussed in this article on the Petrodollar). Because of this, the US is able to print money to fund its own programs without significant devaluation of US dollars. Instead, that devaluation is pushed onto other fiat currencies and citizens around the world.13,14

There is also the fallacy propagated by mainstream economists about the “Horrors” of deflation. However, deflation has the exact opposite effects of inflation including better capital and resource allocation and less risk of inequality for both individuals and countries alike.3

Inflation in our society is purely a monetary phenomenon caused by the creation of new units of fiat currencies.2 To solve this, all we would need is a fixed monetary system with limited supply. One where the rules cannot be changed by any one entity. One where the rules are known by everyone and where the monetary network is accessible to anyone. A fairer system where everyone part of that network would have to abide by those rules, whether you are a small merchant in a Moroccan Bazaar or the most powerful government in the world. A system that has rules… without rulers…15

References

- Mises L. The Theory of Money and Credit. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute; 2009.

- Hayek FA. Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle. London: Jonathan Cape; 1933.

- Booth J. The Price of Tomorrow: Why Deflation is the Key to an Abundant Future. Vancouver, BC: JBooth Publishing; 2020.

- Friedman M. The Role of Monetary Policy. Am Econ Rev. 1968;58(1):1-17.

- Ammous S. The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2018.

- Taylor S. Global house price growth 2021: Australia and Turkey top world property markets [Internet]. 9News. 2023 [cited 2023 May 18]. Available from: https://www.nine.com.au/property/news/australia-leads-global-house-price-index-highest-house-price-growth/7b09707e-f45e-4973-88cc-d9e5d7c4cd27

- Mankiw NG. The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20(4):29-46

- Bagus P, Howden D, Gabriel A. Causes and Consequences of Inflation. Business Soc Rev. 2014;119(4).

- Burley P, Foster J, editors. Economics and Thermodynamics: New Perspectives on Economic Analysis. Springer; 1993.

- Sieroń A. Money, Inflation, and Business Cycles: The Cantillon Effect and the Economy. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2019.

- Balae Z. Monetary Inflation’s Effect on Wealth Inequality: An Austrian Analysis. Quart J Austrian Econ. 2008;11:1-17.

- Reinhart CM, Sbrancia MB. The Liquidation of Government Debt. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper No. 11-10; 2011 Apr 14.

- Prasad E. The dollar trap: how the US dollar tightened its grip on global finance. Princeton University Press; 2014.

- Markets Decoded. How is inflation exported? The Biggest export of the United States [Internet]. YouTube; 2023 May 24 [cited 2023 May 24]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mo6A7Q2Vum8.

Nakamoto S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2023 May 24]. Available from: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

These articles were designed to make these concepts more palatable. If you’re interested in reading a more in-depth perspective on Austrian Economics (a.k.a. economics), consider the following:

Mises Institute. “Economics for Beginners” https://mises.org/economics-beginners

Amous Saifedean. Saylor Academy “Econ103: Principles of Austrian Economics”, https://learn.saylor.org/course/ECON103

Mises, Ludwig Von. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Scholar’s Edition 1998

Friedman M. Price Theory. 2011

Ruki is a passionate Bitcoin educator who firmly believes in the principles of the Austrian School of Economics. As a sound money advocate he recognises its benefits to individuals and society as a whole. He is dedicated to empowering those without financial access to take control and build a more secure future.