Austrian economics is a school of economic thought that emphasizes the importance of individual action, market processes, and subjective value.1 At the heart of this approach lies the idea that prices are not determined by objective costs, but rather by the subjective valuations of buyers and sellers in a given market.2 In this article, we delve deeper into the distinctions between cost, price, and value, and explore how understanding these concepts can shed light on the workings of Austrian economics.3 We examine how the interplay of supply and demand, along with the subjective preferences of market participants, shapes the prices that emerge in a market.4

Keynesians & the unintended benefits of property destruction

What is price and what is cost? Many people argue that these could be considered one in the same. To explain these terms, lets start by delving into an example.

Imagine there’s a baker in a town going about his day. To his misfortune, a kid on the street accidentally throws a baseball through his window, shattering it and leaving a big hole in the front of his store. The baker is understandably upset but is comforted by an economist walking by, who encourages him to see the larger picture. He goes on to explain to the baker that he will have to purchase a new window from the glass store. This purchase will benefit the glass store who will then have to go on to purchase materials for the repair and pay its workers. Perhaps some of these workers end up buying some of the bakers’ bread. So this act of destruction is not really a tragedy, but an event that will benefit the local community and others!

Is the glass breaking actually beneficial for the town overall, or was the bakers’ initial sentiment of sadness correct?

Opportunity Cost

Now let’s think about what would have happened had the window not broken. The baker would have both his window and his money, which he could have spent in other ways. Perhaps he would have bought a new sign for his business or a new suit for himself. The gain for the glassmaker was a loss for the sign maker or tailor. This was the opportunity cost lost.5 Price is what the baker paid, but the cost is what the baker had to “give up”.

If the mistake in the economists’ argument above was obvious to you, you may be surprised to learn that this is the line of thought for a lot of economists today. This is including those that provide advice for government policy. Paul Krugman, a well-known economist and Nobel prize laureate that writes for the New York Times, argues that events such as the September 11 attack and natural disasters are actually a net benefit for economies.6 What Krugman and others fail to understand is that the companies that benefit from such events do so at the loss of other companies making it, at most, net neutral to an economy and overall tragic for that community.

When we decide to make a purchase, we are simultaneously forgoing all other possible purchases that could have been made with that sum of money. This is the cost of our economic decisions.4 Governments and Keynesian economists alike have a hard time thinking about opportunity costs in this way. It’s easy for taxes to be spent on a football stadium because governments can point to a big game and say “Look at what your taxes paid for”. What no one can see are all the things the public lost because of the taxes the government placed on them in the first place.

Value is attained at the Margin

This is a concept that can be agreed upon by both Keynesians and Austrians alike and an important one. If you were a Marxist, you would believe that value was determined by the cost of labour and materials.8 For example, if you spent money on expensive ingredients and hired the best chef, you should then be able to produce a very expensive meal. Marx would argue that the food is valuable because the ingredients and chef were valuable.

Marx used this point to argue that the basis of surplus profits in capitalist economies came from the exploitation of labour.8 He was wrong. We understand utility is what gives something value and so value can only be achieved once the good is created and is useful. The value of the materials and labour is created in reverse.

For our chef example, value is attained at the margin. That is, you pay a lot of money for the meal because the meal is good! Because the meal is good, the chef is in demand and is expensive to hire, and the ingredients are valuable because of the amazing meal that could be made with them. It was the meal that gave the chef and the ingredients their value. Before the amazing meal existed, both the chef and the ingredients used would not be worth as much.

The Subjectivity of Value

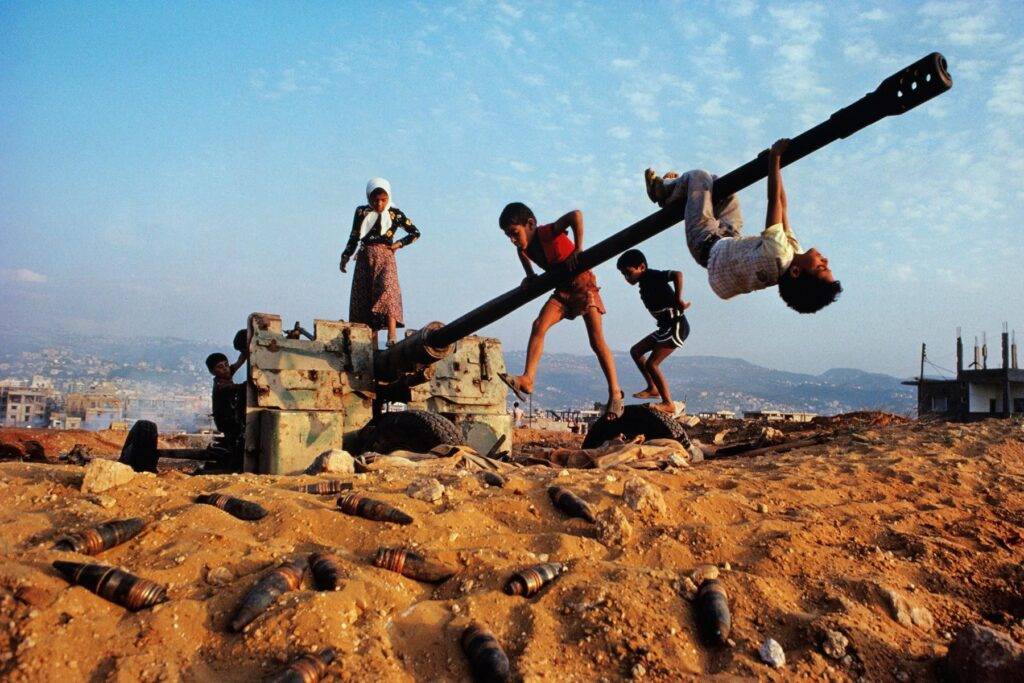

Photography is an incredible art that can be inspiring, insightful and powerful. The above photo was captured by one of the photographers that inspires my own photography, Steven McCurry. Amongst the chaos of war-torn Beruit, Lebanon, these children find a use for a destroyed Anti-tank gun. A very powerful image in many ways but also depicts how different people can value the same thing differently.

Interestingly, after having this discussion amongst a variety of people from all backgrounds, most people appear to instinctively feel value is subjective. If you feel the same way, you would be correct. Keynesians would argue that there is some component of objectivity in value7, where Austrian economists argue value is entirely subjective1. So let’s break down instinct into theory as to why value is entirely subjective.

In the previous article, we established that the value of a good is linked to its utility or how useful that good is to an individual.1 Already there is clear subjectivity to value because utility itself is dependent on the individual. A motorcycle may be immensely useful to someone who knows how to ride it but less useful to anyone that doesn’t.

The very act of making a trade is reliant on value being subjective. If you were in a bookstore and purchased a book for $10, is the value of the book $10? Let’s break down the purchase. If you purchase that book, you are giving up $10 in exchange for the book. This means that you value the book more than you do the $10 (Book > $10). Conversely, the store is happy to give up the book in exchange for $10 because the store values the book less than $10 (Book < $10). If you or the store valued the $10 and book equally then you would be indifferent to the exchange and the trade would not take place. Trade itself only occurs when there is a subjective difference in value between both parties.4 It’s important to realise that both parties are neither right nor wrong in their perceived value because utility and value are dependent on the individual.4

Conclusion

Understanding the concepts of cost, price, and value can help shed light on the workings of economics. The interplay of supply and demand, along with the subjective preferences of market participants, shapes the prices that emerge in a market. Moreover, the subjectivity of value is crucial in understanding economic decisions and how trade occurs.

Value is entirely subjective, and its determination is dependent on individual utility. By grasping these key concepts, we can develop a more profound appreciation of the role of individual choice in shaping economic outcomes. We’ll discuss the concept of diminishing marginal utility in the next article.

References

- Menger C. Principles of economics. Auburn (AL): Ludwig von Mises Institute; 2007.

- Hayek FA. The use of knowledge in society. Am Econ Rev. 1945 Sep;35(4):519-30.

- Rothbard MN. Man, economy, and state: a treatise on economic principles. Auburn (AL): Ludwig von Mises Institute; 2009.

- Mises L von. Human action: a treatise on economics. Auburn (AL): Ludwig von Mises Institute; 1998.

- Buchanan JM. Cost and choice: an inquiry in economic theory. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund; 1999

- Krugman P. Reckonings; after the horror. The New York Times. 2001 Sep 14 [cited 2023 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/14/opinion/reckonings-after-the-horror.html

- Keynes JM. The general theory of employment, interest, and money. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company; 1936.

- Marx K. Wage labour and capital. In: Tucker RC, editor. The Marx-Engels reader. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1978. p. 203-17.

These articles were designed to make these concepts more palatable. If you’re interested in reading a more in-depth perspective on Austrian Economics (a.k.a. economics), consider the following:

Mises Institute. “Economics for Beginners” https://mises.org/economics-beginners

Amous Saifedean. Saylor Academy “Econ103: Principles of Austrian Economics”, https://learn.saylor.org/course/ECON103

Mises, Ludwig Von. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Scholar’s Edition 1998

Friedman M. Price Theory. 2011

Ruki is a passionate Bitcoin educator who firmly believes in the principles of the Austrian School of Economics. As a sound money advocate he recognises its benefits to individuals and society as a whole. He is dedicated to empowering those without financial access to take control and build a more secure future.